First, let me define cold war as a state of political tension and military rivalry between nations that stops short of full-scale war. Second, I’d like to categorize “cold warriors” into two separate groups. I’ll call the first, the Military Group; and the second, the Strategic Group. Both had extremist factions. The Military Group included a subtype I’ll call the Warmongering Group, while the Strategic Group included a subtype I’ll call the Intelligence Group.

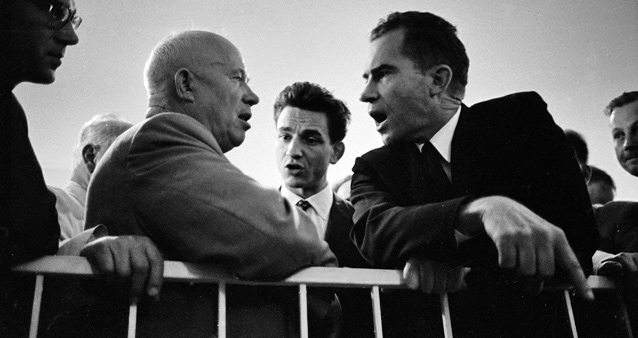

The Warmongering Group included men such as General Curtis LeMay, who wanted to wage war at nearly every turn, but grudgingly resisted the temptation due to the required subservience to civilian Commanders-in-Chief. Those of his ilk favored the use of overwhelming military force all the way up to—and even including—the preemptive use of limited nuclear weapons. They preached this gospel loudly in the hopes that the other side would not dare tempt fate. So, in that sense, the Warmongering Group consisted of individuals who were still only cold warriors because they preferred to avoid a nuclear exchange notwithstanding their saber rattling rhetoric to the contrary. This strategy was very similar to that used by hardliners in the Kremlin and demonstrably evident in Nikita Khrushchev’s behavior, as well. It redefined the word “peace” through an Orwellian twist. Henceforth, “peace” would be equated with a balance of terror through mutually assured destruction. However, that strategy would be effective only if convincingly sold by each side to the other. And therein lay the danger; not only because such tension could potentially escalate to all out war, but because such tension—even absent war—undermines the joy of liberty.

The second group of cold warriors, the Strategic Group, were much more cerebral, calculating and shrewd than their warmongering counterparts. John Kennedy was more closely aligned with this second type upon entering the White House. He surrounded himself with advisers whom he believed were of a like mind, such as, Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, Averell Harriman and McGeorge Bundy, to name but a few. But there always existed a gentler side to JFK. Thus, he incorporated the perspective of historian, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. and the progressive wisdom of speech writer, Ted Sorenson, to instruct his policy. And their influence did instruct his policy.

The more radical subtype of the Strategic Group, namely, the Intelligence Group included people like Allen Dulles, Dick Bissell, Ed Lansdale and others. This group consisted of those who believed that American interests were best served diplomatically when possible—however, in the event of diplomatic failure—then through the use of espionage, propaganda, insurgency, sabotage, election rigging, and even coup détat (assassinations). Some of the characters, mainly from the State Department, appeared moderate on the surface when, in fact, they were more closely aligned with the hardliners within the Intelligence Group.

The Intelligence Group was adept at employing non-military strategies in a manner sufficiently effective to advance the interests of the United States, but whose activities often could not be sanctioned by the United States Government due to their sometimes-criminal nature. This gave rise to, what I term, the Doctrine of Plausible Deniability; the notion that if an action was deemed necessary to advance the interests of America it was justified—irrespective of its criminal nature—provided it could be plausibly denied. Sad, but true. In any event, it is no wonder that a “necessarily secretive environment” spawned a culture both disinclined toward full disclosure to the President as well as one that was resistant to cooperating with Congressional oversight. Moreover, their services began to be tapped by powerful members of Congress, the Cabinet, and private interests both within and without the military/industrial complex.

It is from within this context that the young President’s own foreign policy originally derived. One of the key advantages Kennedy enjoyed was perspective. As the son of a former Ambassador to the Court of Saint James he had traveled internationally from a very young age. He was also quite aware of the isolationist policy that his father had embraced prior to Pearl Harbor during the Battle of Britain and how badly that had damaged his father’s own personal political ambitions. While the political realities associated with being viewed as “soft on Communism” impacted Kennedy’s political persona, it did not change his core beliefs in terms of what American resistance to Communist aggression should and should not entail.

Kennedy was more or less of an Atlantic or European orientation as opposed to a Pacific Rim orientation. Nonetheless, he did speak out quite forcefully against a ground war in Southeast Asia while still a Congressman, which turned out to be the correct course. Not only did he learn from the past mistakes of former presidents who had unsuccessfully attempted to win ground wars waged in Asia—Truman in Korea comes to mind—but he also had the more recent failure of France to win its campaign in Vietnam to remind him of the folly of such an endeavor. Indeed, Charles De Gaulle told Kennedy in early 1961 that the United States would go “step by step into a bottomless quagmire, however much it spent in men and money” if it attempted to save South Vietnam from Communism. But Kennedy already knew, prior to De Gaulle’s warning, not to get entangled in Vietnam. As early as November of 1951 JFK reported, upon his return from a Far East fact-finding trip, that our continued support of the French effort was futile and those efforts to contain Communism through force, rather than persuasion, would fail. He already was highly critical of any approach that failed to enlist the genuine support of the native peoples of Vietnam. Then, 3 years later, on April 6th, 1954 as a Senator, in his response to then Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’ pitch for American intervention in Vietnam, Kennedy argued against it, saying:

“…To pour money, materiel, and men into the jungles of Indochina without at least a remote prospect of victory would be dangerously futile and self destructive. Of course, all discussion of United States action assumes the inevitability of such victory. Such assumptions are not unlike similar predictions of confidence, which have lulled the American People for many years. I am frankly of the belief that no amount of American military assistance in Indochina can conquer an enemy which is everywhere and at the same time nowhere; an enemy of the people which has the sympathy and covert support of the people.” He went on to say that if the French persist in refusing to grant the people their independence and if the surrounding nations continue to remain aloof (which they did): “Then it is my hope that Secretary Dulles will recognize the futility of channeling American men and machines into that hopeless struggle.”

The wisdom that Jack Kennedy brought to the White House was not trivial. It was a balanced approach of progressive conservatism from the start. However, unlike that of his political rival, Richard Nixon, his policy was both flexible and adaptable to the demands imposed by a world that was only then becoming fully aware of its nuclear capability.

In the corridors of the Pentagon war had historically been viewed as a zero-sum game where the gains of the victorious are perfectly balanced against the losses of those who had been met with defeat. In war’s aftermath, to the victor went the spoils, as did the privilege of recording the history of the event itself. But in the post WWII era there would potentially be no spoils remaining following a nuclear exchange and thus neither side would emerge as victorious. Indeed, there was doubt as to whether any survivors would remain to write the history of the event at all.

By the 1960 election, change was in the wind. Following JFK’s inaugural address in January of 1961, the American people were inspired and motivated. They were “asking what they could do for their country” and volunteering for public service in record numbers. America was notably optimistic, confident in its young leader’s wisdom and ready to carry the torch. But bureaucracies move slowly and adapt only when forced to do so. Thus the available options remained limited to two: either a state of actual war or a state of cold war would exist between us and our adversaries, so stubborn was the nature of the hawks in the Pentagon, the CIA, the State Department and elsewhere. Since actual war could escalate into Armageddon, cold war was seen as the only remaining viable option.

The Intelligence Community had been handling cold war matters ever since the end of the Second World War. However, during the lame duck period following the 1960 election, Richard Nixon had both fueled the build-up of anti-Castro Cubans into Brigade 2506 and blocked the operation from proceeding during the Eisenhower Administration. CIA’s Jake Esterline placed most of the blame for the Bay of Pigs on Nixon’s failure to launch the invasion by the end of 1960. Nevertheless, by the time Kennedy took office the size and scope of the invasion plan was, far and away, the largest operation ever attempted by the CIA. It had grown to military proportions. The CIA is not proficient at military-sized operations.

Feeling betrayed by the CIA for the fiasco at the Bay of Pigs, President Kennedy removed the authority to conduct cold war operations from the CIA and turned it over to the Joint Chiefs by signing National Security Action Memorandums 55, 56 & 57. While it’s true that the military was good at waging actual war, it was unprepared—indeed ill suited—for the demands of cold war operations. Colonel L. Fletcher Prouty, USAF (former Chief of Special Operations) was the officer tasked by President Kennedy to brief the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Lyman Lemnitzer, as to the meaning of these memoranda. According to Prouty’s assessment:

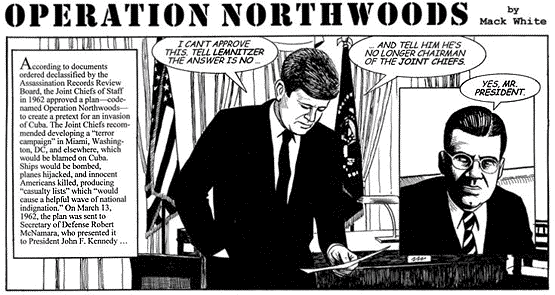

By 1962 Colonel Prouty’s observation was proved accurate. The military had come up with Operation Northwoods in which the initial action would be launched in a covert or “cold war” consistent manner through a false flag attack carried out by the CIA. That is where the “fun and games” would end. This false flag attack would then allow the President the ability to exercise his authority as Commander-in-Chief and order the military to retaliate. Thus the “operation” would have quickly evolved from “special” (covert) into one with which the military was more comfortable: combat (overt). But that defeated the purpose. It became evident that not only was the CIA incompetent at military-sized operations, as evidenced at the Bay of Pigs, but that the military was equally incompetent at clandestine operations, as evidenced by Operation Northwoods, which Kennedy rejected.

Gradually, Kennedy began to back away from cold war mentality completely. He began to see that there was a third option that itself existed beyond war, cold or actual. It was the option for peace. He sought to foster peaceful solutions through finding common ground with adversaries. “We all share this small planet…” He sought to foster peace through proposing cooperation with our adversaries in overcoming challenges to the common goals of all of mankind. He proposed that we spend our time and resources, not on war or preparations for war, but on fighting the common enemies of man: hunger, poverty, disease and ignorance. He proposed increased exposure to the arts; he noted the thrill of exploring different cultures with a mind toward what we have in common and a genuine interest in that which we do not; he proposed cooperation with the Soviet Union in space exploration and joint lunar landing missions (NSAM 271); and he created the Peace Corp. President Kennedy’s goals were ambitious, but not unreasonably so. His vision was not just good for that time, but also good for our time, and perhaps, for all time. If his call for cooperation between otherwise competing nations had been answered during his second term, imagine how much farther we would have come by now? His was truly a revolutionary mind.