Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip: A Monstrous Distortion of History

A Book Review by James Norwood

Annie Jacobsen’s 575-page Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America (Little, Brown and Company, 2014) combines documentary evidence with extensive interviews in a compelling work of history. Here is an example of a mainstream book publication that examines the burgeoning secret government America in the aftermath of World War II. It is also a work that deals with facts, as opposed to “theories.” As a model of inquiry into a controversial historical topic, Jacobsen’s study reveals how it is possible to untangle a complex event in order to shed light on how our nation was transformed from within in the second half of the twentieth century.

Annie Jacobsen’s 575-page Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America (Little, Brown and Company, 2014) combines documentary evidence with extensive interviews in a compelling work of history. Here is an example of a mainstream book publication that examines the burgeoning secret government America in the aftermath of World War II. It is also a work that deals with facts, as opposed to “theories.” As a model of inquiry into a controversial historical topic, Jacobsen’s study reveals how it is possible to untangle a complex event in order to shed light on how our nation was transformed from within in the second half of the twentieth century.

“Operation Paperclip” was the code name given to the top-secret program to recruit Nazi scientists and doctors in the chaotic period at the close of World War II. Among the many new branches of the expanding American military and intelligence network, the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) was formed in 1945 with the express goal of recruiting Nazi scientists to engage in weapons projects, scientific intelligence programs, and chemical/biological warfare. Initially, President Truman was not apprised of the program, which was approved in principle by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on July 6, 1945. Over a year later, Truman gave his official approval after the urging of the undersecretary of the State Department, Dean Acheson. One of the most ardent critics of Operation Paperclip was Albert Einstein, who wrote a spirited letter to Truman on behalf of the Federation of American Scientists. But from the very beginning, the creation of what the author calls a “headless monster” was fully underway with the dual purpose of ending the war with Japan and confronting a new threat from a wartime ally, the USSR, in the areas of chemical, biological, and atomic warfare. A Faustian pact was made to ignore the ignominious past deeds of war criminals with the ultimate goal of winning the Cold War.

Ms. Jacobsen is successful in linking names and faces to Operation Paperclip. As most of the documents have long been destroyed, especially during the stewardship of CIA director Richard Helms, it is remarkable that the author has discovered enough evidence for a book of this scope through interviews and Freedom of Information Act requests, as well as the ground-breaking work of previous investigators like Linda Hunt. Ms. Jacobsen provides a rogues gallery of photographs of the elite Nazi scientists, researchers, and medical practitioners. A number of the men have scars on their faces, the result of the pastime of dueling for the Nazi top brass. One photo depicts a dueling scene occurring near the site of the Auschwitz death camp. Short biographical portraits are presented of both the scientists and the American military officers who recruited them. A number of heroic figures, such as State Department officer Samuel Klaus and a relentless investigator of war crimes, Dr. Leopold Alexander, strongly resisted the Nazi scientist program.

Due to the early efforts of journalist Drew Pearson, there was initial public outrage to the prospect of bringing the Nazi scientists to America. But with the passing of the National Security Act on July 26,1947, and the establishment of the CIA, the most intimate details of Operation Paperclip were kept secret from the American public for decades. As indicated by Ms. Jacobsen, “In Operation Paperclip, the CIA found a perfect partner in its quest for scientific intelligence. And it was in the CIA that Operation Paperclip found its strongest supporting partner yet.” (p. 288). Such secret CIA spin-off programs as Artichoke, MKUltra, Bluebird, and others would focus on “mind control,” “modifying behavior through covert means,” and “extreme interrogation” by using experimental drugs, such as LSD. In 1946, Reinhard Gehlen was recruited, not as a scientist, but for his expertise as former chief of Nazi intelligence against the USSR. The so-called Gehlen Organization was subsequently absorbed into the cavernous network of the CIA. Operation Paperclip was the tip of the iceberg for seemingly unlimited and unrestrained covert CIA operations.

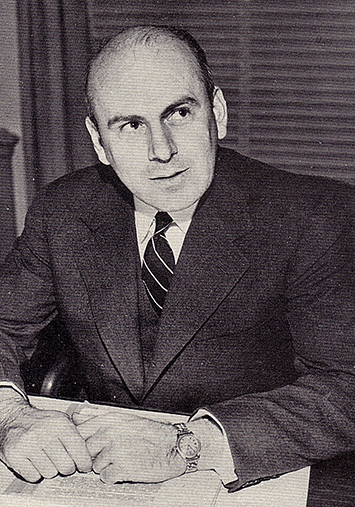

A prominent civilian who made Operation Paperclip a full-blown operation was the future member of the Warren Commission, John J. McCloy. From 1945, when he was assistant secretary of war, to his role as chairman of the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee, and finally, to the time of his appointment as U.S. high commissioner of Germany in 1949, McCloy used his authority to champion the Nazi scientist program. From his headquarters in Frankfurt, McCloy’s office was located just a few floors up and a few doors down from the CIA office in the same building. According to Ms. Jacobsen, McCloy was advised by his legal staff that as high commissioner that “he had the authority to do whatever he thought appropriate.” (p. 337). McCloy proceeded to commute ten of fifteen death sentences from a batch of condemned criminals housed in the Landsberg Prison. In another notorious case, McCloy released from prison the industrialist Friedrich Flick, who had been tried and convicted at Nuremberg, then went on to become the wealthiest person in Germany during the Cold War. McCloy even attempted to commute the prison sentence of Albert Speer, one Hitler’s most loyal henchmen.

One of McCloy’s prize recruits was Otto Ambros, the Nazi chemist who had discovered sarin gas. Convicted of mass murder at the Nuremberg trials, Ambros was granted clemency by McCloy, prior to signing a Paperclip contract and helping America build an arsenal of sarin on an incredible scale. At the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, thousands of tons of sarin nerve agent were manufactured annually. The principal method of delivery was through M34 cluster bombs, which would be filled with sarin gas. It was not until November 25, 1969 that President Richard Nixon declared the end of the American biological warfare program and ordered the destruction of its enormous arsenal. According to Ms. Jacobson, it took more than three decades to “destroy” a stockpile of chemical weapons at a cost of $25.8 billion.

In the story of Operation Paperclip, an essential reference point for Ms. Jacobsen is the Nuremberg Code, which was the result of the war criminal trials conducted in Germany by the allies. Dr. Alexander was instrumental in providing a template for moral principles that were eventually expanded to six points of ethical conduct in medical research. At the core of those principles was the requirement in absolute terms of “informed consent” and “absence of coercion” for human beings used as subjects in medical experiments. But during the Nuremberg trials, Operation Paperclip was recruiting scientists who were guilty of the very war crimes that brought the Code into existence. As indicated by Ms. Jacobsen, “Less than 150 miles from the Nuremberg courtroom, several of the physicians who had participated in, and many others who were accessory to, these criminal medical experiments were now being employed by the U.S. Army at the Army Air Forces Aero Medical Center, the classified research facility in Heidelberg.” (p. 203) In the ensuing decades, the principles of the Nuremberg Code continued to be violated in the use of human subjects as guinea pigs with no regard to the concept of informed consent.

Ms. Jacobsen highlights the tragic case of Dr. Frank Olson as a flagrant violation of Nuremberg Code. Dr. Olson was a specialist in biological warfare, who became an unwitting guinea pig for Dr. Sidney Gottlieb’s experiments with LSD as part of a top secret CIA program. On November 18, 1953, after drinking a glass of Cointreau spiked with the drug, Dr. Olson had a nervous breakdown. Two weeks later, he allegedly committed suicide, hurtling himself through the window of a room in the tenth floor of the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City. According to Ms. Jacobsen, the death of Dr. Olson “would nearly bring down the CIA.” (p. 366). But in the year following this incident, the CIA enjoyed two of its greatest “successes” in the overthrow of democratically elected regimes in Guatemala and Iran through carefully planned coups d’état. With its unprecedented and unaccountable authority, the CIA experiments in mind control in Project MKUltra would continue unchecked for another two decades.

In summing up the significance of Operation Paperclip, Ms. Jacobsen places the program in the context of the Cold War:

“The Cold War became a battlefield marked by doublespeak. Disguise, distortion, and deception were accepted as reality. Truth was promised in a serum. And Operation Paperclip, born of the ashes of World War II, was the inciting incident in this hall of mirrors.” (p. 175)

In this carefully researched study, it becomes apparent that Operation Paperclip opened the floodgates to a new, secret government that subverted our democratic practices while wielding power without the traditional checks and balances of our Constitution. The nuclear physicist Herbert York was the first scientific director of the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). York was troubled by the implications of President Eisenhower’s farewell address in which the outgoing chief executive warned not only of the dangers of the “military industrial complex,” but the potential abuses of scientific research: “In holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.” When York later questioned Eisenhower about what individual scientist had aroused his concerns, the retired president identified Wernher von Braun—one of the earliest recruits into Operation Paperclip and the eventual superstar of the American space program. Von Braun was transformed into an American patriot and hero, resulting in part from a series of articles in Collier’s magazine and a popular television series produced by Walt Disney. As the author makes clear, propaganda played a crucial role in defusing the implications of Operation Paperclip.

One of the themes of this extremely detailed study is how the process of decision-making in America was taken away from elected officials and managed in secrecy in the labyrinth of the American intelligence network. Studying this topic reveals a world of concealment and obfuscation contrary to our cherished democratic practices. As Ms. Jacobsen observes, “Through the lens of history, it is remarkable to think that U.S. biological warfare and chemical warfare programs grew so quickly to the size they did.” (p. 391). The subversion of our political system was achieved in large part through the ability to “classify” documents and to rely on a compliant media to distort the historical truth, which was buried in unprecedented governmental bureaucratic secrecy and obfuscation. While serving as president, even Ronald Reagan could not get straight answers or documentation about the circumstances of Otto Ambros’s work in American industry.

While many of the secrets of Operation Paperclip were jealously guarded, the truth has a way of emerging, especially with the dedication of a gifted writer and tenacious researcher like Annie Jacobsen. One of realities conveyed by the author was the postwar obsession to acquire “science at any price.” The result was the creation of a national security Frankenstein with whom we are still wrestling today. The necessity of hiding the secrets of the “headless monster” has led to the concealment of the truth from the American public in a manner that has now become routine. The noted French Resistance writer Jean Michel observed that, “I make my stand solely against the monstrous distortion of history which, in silencing certain facts and glorifying others, has given birth to false, foul and suspect myths.” (p. 425) Annie Jacobsen’s book goes a long way to setting the record straight and challenging one of many “myths” about our recent history. In this regard, Operation Paperclip is a paradigm for understanding what happened to America during the Cold War.